AI Empowers Early Diagnoses: How Artificial Intelligence is helping physicians diagnose skin cancer

January 26, 2024

By Laura Eggertson

When social worker Marie Kavanaugh caught sight of a big yellow poster at the IWK hospital advertising a research study investigating skin cancer, she had no idea her impulse to enroll would save her life.

students at Dalhousie, was a good way to get her skin examined just in case.

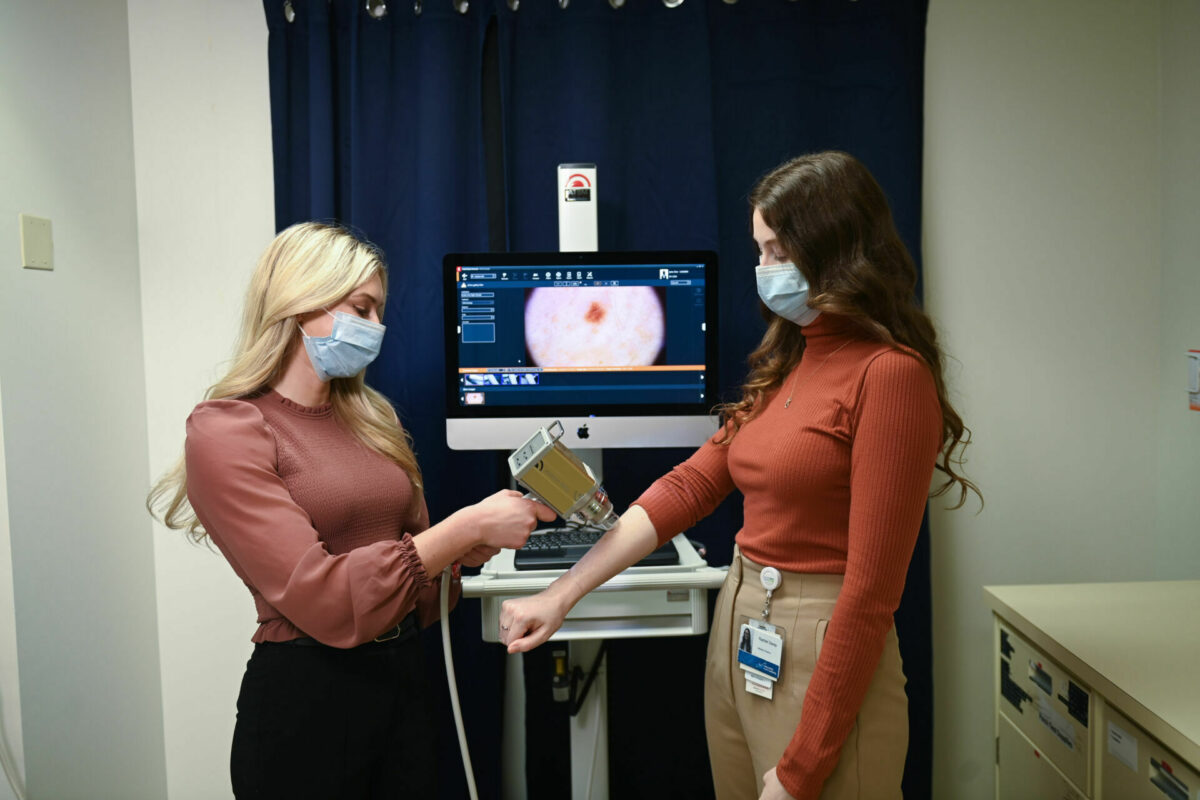

Madeleine Crawford and Rachel Dorey are two of the students who worked on the study, using Artificial Intelligence as a Melanoma Screening Tool in Self-Referred Patients, under the supervision of Dr. Peter Hull, a Dalhousie professor, researcher, and a dermatologist.

The study tested the ability of an Artificial Intelligence (AI) program to analyze scanned images of lesions and detect melanoma and other skin cancers, compared to

the ability of dermatologists examining the same images.

The purpose of the study was to determine if the AI device, called FotoFinder Moleanalyzer Pro® Version 6.0, would work “as a screening tool to help alleviate the barrier patients are currently facing to have lesions of concern examined in a timely fashion,” says Crawford.

In Nova Scotia, which has one of the highest rates of skin cancer in Canada, Crawford and Dorey knew one of the critical barriers to detecting melanoma early is that nearly 20 per cent of the population lacks a family doctor.

There are also long wait times to see a dermatologist, not only in Nova Scotia but throughout the Maritimes. The wait times are particularly troubling because skin

cancer can spread quickly.

EARLY DETECTION IS KEY

“Melanoma can potentially lead to death if it is not caught early and treated in its early stages,” says Crawford. “However, when melanoma is detected in its early stages the prognosis is quite good and it is curable.” Kavanaugh was one of 318 participants in the study. Those participants had 381 “lesions of concern” between them. In total, 17 of those lesions were skin cancers, including 10 melanomas.

The study concluded the FotoFinder device was accurate in flagging cancers 74 percent of the time, comparable to the success rates of the dermatologists. The FotoFinder consists of a special camera linked to a computer via a software program whose algorithm is configured to recognize the characteristics of a cancerous lesion.

To Kavanaugh’s shock, a freckle-like spot in the crook of her left arm was one of the early-stage melanomas the software identified. “I was called saying I had malignant melanoma and it had spread to the surface and I needed to have surgery right away,” Kavanaugh remembers.

Within about six weeks of having entered the study, a plastic surgeon had removed the lesion and some surrounding tissue. “I was very, very lucky to have been in this study,” Kavanaugh says.

Early detection was “a game-changer” for Kavanaugh and could be for others, she says. “If I had not signed up, I would not have known I had a problem and I would

never have known the seriousness of my situation.” Dr. Hull and the students believe the accuracy of the AI program could make it an important public health tool. They want Nova Scotia to set up clinics across the province where nurse practitioners could use the device to scan the lesions of patients who refer themselves to get their moles or lesions checked. The nurse practitioners could also excise suspect lesions.

“It would make the system highly efficient and highly cost-effective,” Dr. Hull says of his proposed model. He anticipates it would cost less than $1 million in the first year to set up the self-referral centres, buy the equipment, and pay the nurse practitioners. “What we’re trying to do is diagnose melanoma really early, so we make a difference,” he adds.

NS COULD LEAD

Nova Scotia would be the first province to adopt AI-assisted screening clinics if the provincial government opted to use this type of screening tool as part of the

public system.

Other jurisdictions, including the United Kingdom and New Zealand, are already using AI-assisted applications to screen for skin cancer. In the U.K., general practitioners can access the technology, while in New Zealand, similar programs are available in private clinics. Dorey, who worked on the study alongside Crawford and two other students, expects AI-enabled technology to improve and grow in usage throughout her medical career. That made her eager to learn to use the camera and test the program.

“Getting to see how AI can be used in a positive light to support dermatologists, primary care providers and patients to have access [to care] was very exciting,” she says.

RESEARCH IN MEDICINE

The Sandy Murray Research in Medicine (RIM) studentships supported Dorey, Crawford, and their fellow students Kiyana Kamali and Olivia MacIntyre during the research project. The Allan and Leslie Shaw Research Fund also supported the study.

RIM students choose a mentored research project which they pursue throughout medical school, including an intensive summer internship. Through donor-supported funds, Dalhousie provides $5000 to offset the research project’s costs. RIM projects introduce medical students to the importance of research, in hopes of fostering their interest in clinical research throughout their medical careers. Crawford plans to continue to pursue research as a resident and beyond.

“Research is just so valuable in medicine in order to provide the best patient care, and this study really highlighted that,” she says.

By Laura Eggertson

When Dalhousie medical student Madeleine Crawford began learning to identify suspicious lesions as part of a skin cancer study she was co-investigating, she didn’t realize how close to home her new skills would take her. Crawford’s mother, Elizabeth, heard about her daughter’s work while Madeleine was back home in Stratford, PEI, visiting her.

“I asked her to do a skin check on me,” says Elizabeth Crawford, who leads curriculum development for K-Grade 6 students for Prince Edward Island. To her mother’s surprise, Madeleine Crawford found a tiny spot on her mother’s calf that concerned her.

“You need to go check this one. I don’t like it,” Madeleine told Elizabeth.

Elizabeth Crawford booked an appointment with her family doctor. Because of long wait lists, she didn’t get in to see PEI’s only dermatologist to have the mole removed and biopsied for seven months. That’s when she learned the tiny mole on her calf was an early-stage melanoma.

“I was actually surprised,” Elizabeth Crawford says. “That one wouldn’t have been on my radar.”

While she waited to get the first mole removed, the senior Crawford was living with her daughter in Halifax. Madeleine Crawford continued to perform skin checks on her mother, and found a second suspicious mole.

That’s when she got her mother to enroll in the Dalhousie study. Within five weeks of Elizabeth Crawford’s enrollment, the study also flagged the second mole as needing an excision. Once it was removed and sent to pathology for a biopsy, it turned out to be benign.

“The (second) lesion enrolled in the study was examined, removed, and diagnosed long before the one using our standard healthcare system was—and that one ended up being the melanoma,” Madeleine Crawford says.

The wait time to see a dermatologist in PEI highlights the importance of the early screening tools the Dalhousie study evaluated, Elizabeth Crawford says. Mother and daughter are thankful Elizabeth had a happy outcome.

“She was very lucky that I was able to advocate and educate her on the importance of doing skin checks, especially when we do experience a lack of access (to dermatologists) in Prince Edward Island,” Madeleine Crawford says.

TAGS